To Richard Ford, writing a memoir is to utter what must not be erased

JUDY WOODRUFF:

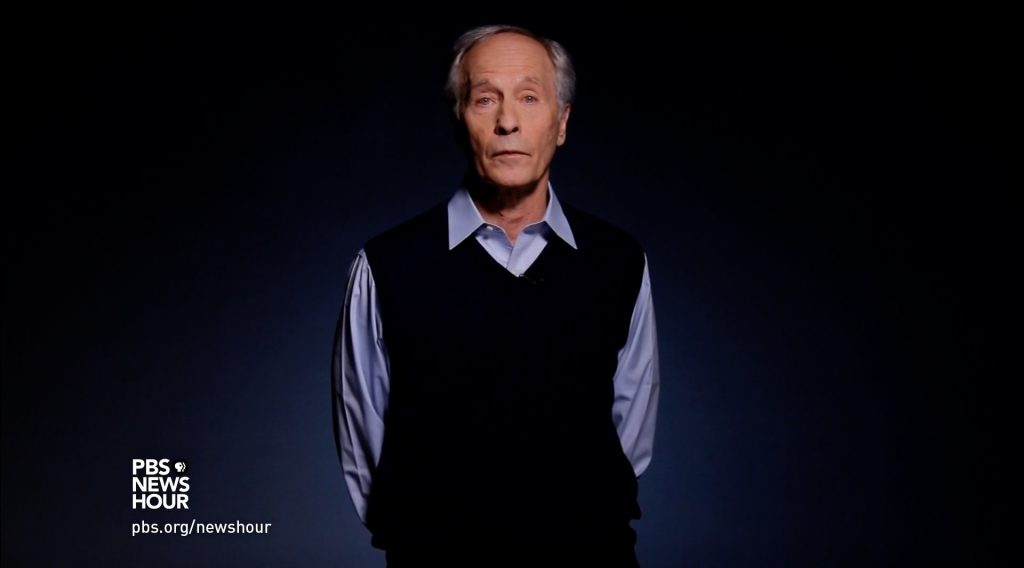

Finally, an essay by author Richard Ford.

His latest book, "Between Them," is a memoir of his parents' lives, and, tonight, he shares his Humble Opinion about taking note of their love.

Have a listen.

RICHARD FORD, Author, "Between Them: Remembering My Parents": Goodness knows, there are lots of reasons to write a memoir, to render testimony, to bear witness, to make sense of a recollected life that had failed to make sense before, to turn to the mysteries of memory and improvise a continuous narrative of our own life, and, in that way, substantiate ourselves to ourselves and others.

St. Augustine told us, memory is a faculty of the soul.

Writing a memoir about my parents, Parker and Edna Ford, didn't seem so much to be writing about myself as about them, although I was their only child, and the only one remaining to say that they'd even existed.

So, here is another reason to write a memoir: to utter what must not be erased.

I wrote about my parents because, decades after their deaths and when I was no longer young, I realized that I plainly missed them and wished, in some way, to draw them near me again. Writing about them would do that, I thought. And it is worth saying that such an emotion, missing them, is possible, and can be acted upon, even long after it might be supposed that enough time has passed for longing to subside.

My parents were wonderful parents, though, other than causing me to happen and making each other blissful for 32 years, they set little in motion and were, as most of our parents are, all but unnoticeable in the world's disinterested eye.

And yet it's fair to say that, because they were who and how they were, being their son seemed a privilege. And, almost mysteriously, they opened for me a world of immense possibility.

The choice to make fictional characters of my parents, which would seem to be what many novelists do, simply didn't occur to me. Fiction's reliance on artifice, its necessity to suspend disbelief in order to assure trust, its engrossing arbitrariness, and its foundation in the provisional, all of these orchestrations of fiction threatened to overpower my parents.

What I wanted, as their son, wasn't for disbelief to be suspended, but for it to be abolished, and for belief in my parents and their lives to become absolute.

Facts, with their blunter, more specific hold on truth, seemed to me the better way to represent my parents as they were, and a better way for me to say that, because of how they were, not in spite of it, they merited the world's attention. That's worth saying, too.

Age is a winnowing process. And, sometimes, what gets sifted out as we seek to know the important consequence of lives are the actual lives themselves. Odd to think that we could, even for a moment, overlook such rudiments or take them for granted.

Memoir is for that, too, its great virtue being to remind us that, in a world cloaked in supposition, in opinion, in misdirection, and often in outright untruth, things do actually happen.

My parents' lives did take place. And it is here, in the incontrovertible truth that facts provide, that our firmest beliefs must first take hold.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejnby4e9GimqGZopl6p7vRnWSwqpmptq%2BzjKacpqeZp3q2wNOeqWalpajBbrrOrWSeqpGosqU%3D